The EU just announced that they have entered into talks with Turkey about the possibility of that country joining the union. Yesterday, the EU was faced with a crisis over whether or not to even discuss membership with Turkey. The chief obstacle, it seems, was Austria. Turkey admonished the Eu over this stating that this crucial moment will show whether the EU has "political maturity and become a global power, or it will end up a Christian club."

It's interesting that Turkish leaders should note such a thing since within their own borders the pull between the modern and the past (or, as Westerners like to phrase it, the Western and the Eastern) has been prominent. Karen Hughes, undersecretary of propaganda for the Bush administration, recently traveled to the Middle East and Turkey. While most press reports focused on Turkish women taking her to task for the U.S. going to war in Iraq, there were also reports that Hughes attempted to criticize the wearing of headscarves by Turkish women as a mode of oppression. The Turkish women fired back that they like to wear the headscarves and that it was their choice to do so.

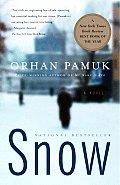

According to Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk's novel, Snow, things are a bit more complicated than what these women suggested. The book is Pamuk's first openly political novel. As such it details tensions within his country between the modern and the past and between Western and Eastern practices and philosophies.

In her NY Times Review of the novel, Margaret Atwood suggested that an argument could be made for the "male labyrinthine novel" and compared Pamuk to Borges, Calvino, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, et al. Having listened to Pamuk discuss his influences during an appearance in Seattle last fall, I'm pretty sure that he would wince at the comparison to Garcia Marquez, but think that the others were fair (he made clear in that appearance that he doesn't think much of the "magic realism" movement).

Atwood is correct in her position. Pamuk weaves plot lines together in such a way as to draw the main character into layers of corridors that cross back and forth and sometimes they cross paths as well, much like the streets and back alleys of some poorly designed city. It's these layers which give his novels the richness they possess. The layers point out associations between moments, symbols, and ideas much the way that the human mind makes such connections as a person wanders through his day. It also leaves this reader feeling that things are more complicated and connected than I sometimes allow myself to imagine - especially as I'm trying to just get through my day with my agenda (or blinders) set in front of me.

For this reason, I love reading Pamuk's books. Initially, I set Snow down and thought that I didn't like it as much as a couple of his previous books. But, now a week away from that moment, I've had time to let the book set in and I'm finding that I like it even more than I had thought. The layers have begun to crystallize and with that they have taken on a new unique beauty that my first observations had missed.

The story in Snow revolves around a Turkish poet living in exile in Germany named Ka. Ka has returned to Istanbul for his mother's funeral. While there, he reacquaints himself with an old journalist friend who convinces Ka to travel to the city of Kars where a series of suicides has taken place by young women who wear headscarves. Ka's friend wants the poet to report back on what he finds there about why these women should turn their backs on the faith they claim to uphold by committing suicide. Though he doesn't realize it at the time, Ka agrees to go along on the trip so that he may fall in love and bring a Turkish wife back to Germany with him, where he has been living a solitary and lonely existence.

While on the way to Kars, the snow of the novel's title begins. Eventually, it will blanket Kars, blocking all passage into and out of the city. The labyrinth has closed and now the reader gets to watch as the characters run through the maze. At first, Ka earnestly begins to investigate the deaths of these women. He talks with the local newsman, with parents and relatives of the women and with some of their friends. It isn't long, however, that he sees that his real purpose is to fall in love with an old acquaintance. As he does so, it is this love that blankets his heart and drives hi. He pays less attention to other events as he just wants to live through the days until the snow melts and he and his love can return to Germany together.

Of course, these other events are significant and frightening. Within hours, he and his love witness the murder of a local educator by a Muslim fundamentalist upset that the teacher wouldn't allow the headscarf girls into his school while they wore the veil. Ka then goes on to face a police interrogation, an infamous Muslim fundamentalist rebel, Muslim students, a cleric leader, the police several times, and live through a secularist coup staged by an actor and his wife who are passing through town. While in the midst of these fearful plot twists, Ka is very much aware of the danger and fear he feels. However, as soon as the immediate danger passes, Ka walks out into the streets of Ka and it's inevitable snow.

Snow here is used as a metaphor. It is at once the underlying melancholy of the situation, the ever present danger in the city of Kars, and the love and happiness that Ka feels as he walks through that city. Such is the richness of this labyrinthine novel that it allows this symbol to portray all three concepts. Just as Ka is feeling scared and wants to run, he allows his mind to get caught up in the beauty of the snow and he feels happy, if not at peace again. For the first time in 4 years, Ka is able to write poems again. He is prolific and writes 19 poems over a two day period. He begins to realize that his poems can be laid out logically in a pattern that resembles a graphic drawing of a single snowflake and he uses this symbol as his guide. It is yet another layer for the book.

As Ka traverses this tale, the reader already is aware of it's tragic ending. This lends to the reader's feeling of the melancholy of Ka's story. It is only a matter of how we get from point A to point Z that matters. Pamuk is such a good writer that I care about the journey along the way and took great delight in getting there. It was inevitable that as the snow melted and allowed Ka to leave the city, his tale of would conclude without a happy ending.

Through this book the reader is exposed to the complicated cultural and political views within Turkey. Socialists, nationalists, Muslim fundamentalists, secularists, and Kurdish nationalists are all portrayed in the story. The headscarf girls are themselves a rather complicated lot. Some of them began wearing the veil merely because they wanted to do so; some for devout religious reasons. It is only when the government demands that they take off the headscarves in order to attend school that the wearing takes on a greater role - one of political statement - that leads them down a tragic path.

At a time when a political crony from Washington is traveling to the Middle East lecturing women on their culture and at a time when the EU is opening it's arms to Turkey's membership, reading Orhan Pamuk's novel Snow feels quite relevant. For people interested in the politics and culture of that region of the world, I highly recommend the book.

As a rather interesting edge, where life imitates art, at one point in the book Ka us interrogated over his acknowledgment of the Armenian killings at the turn of the 20th century in Turkey. Armenians have long contended this was a genocide while Turks have maintained that it was a bloody civil conflict with large numbers of dead on both sides. Ka is warned that to discuss such things, particularly in the Western press, can be seen as spreading negative propaganda which is a crime against the Turkish state. Pamuk did such a thing himself earlier this year in an interview with a Swiss reporter. He has been accused of the same crime and awaits trial within his country. No doubt that this will add fire as the debate over Turkey's EU membership carries on. And so, the novelist who wrote of Ka (and in fact includes himself as the narrator of Ka's story) now finds himself in his own labyrinth of political intrigue.

No comments:

Post a Comment